This is a guest blog post by Holly, a school-based SLP, all about summarizing and main idea intervention!

“Tell me about that movie you watched!”

“What are you learning about in social studies?”

“Let’s summarize what we learned from this article.”

These types of conversations can take a lot of effort for our students.To provide a summary, countless foundational language skills are involved: comprehending information, remembering details, categorizing based on topics and themes, sequencing, identifying story elements, filtering important and unimportant information, paraphrasing, formulating sentences — the list goes on!

It’s no wonder this skill is so challenging and important. What makes summarizing such a powerful target for language intervention? It’s:

Relevant. Summarizing is a curriculum-based skill that shows up in Common Core standards all the way from kindergarten (retell familiar stories with support) to twelfth grade (provide an objective summary of the text).

Functional. Students have opportunities to practice it across everyday conversations, language arts instruction, and nearly every other academic content area!

Strategic. Not only is summarizing a skill in itself — it’s a helpful tool to support memory, comprehension, and expression. We’re all for working smarter (not harder) and that counts for our students, too.

This is why we’re reviewing practical strategies for summarizing and main idea intervention. While this is an area that is well-researched in the field of education, our goal is to help you filter through the information to find high-quality, relevant external evidence and explore how it fits into your own decision-making.

Thanks to ASHA’s Evidence Maps, this post’s primary source is a systematic review and meta-analysis by Stevens, Park, & Vaughn (2019). The article investigated interventions for summarizing and main idea identification, which were provided to struggling readers from elementary school to high school.

The Difference Between Retelling and Summarizing

When a student retells a story, they are using story grammar to recount a series of events.

When a student summarizes a text, they are identifying the main idea and key details. The text is expository in nature (versus a narrative).

Here are the highlights…

This systematic review included 30 experimental, quasi-experimental, or single-case design studies published between 1978 and 2016, with a population of students between third and twelfth grade who were identified as struggling readers.

The interventions included a range of summarizing and main idea instructional practices (using a mix of narrative and expository texts), administered across a range of service delivery models (1-4 students per group vs. 5+ students per group, 12 and fewer sessions vs. 13 and more sessions).

The outcomes of the group design studies “were indicated to have a positive effect on struggling readers with an effect size of 0.97” and the single-case design studies “demonstrated strong evidence favoring main idea and summarizing interventions on oral and written retell measures” (Stevens, Park, & Vaughn, 2019). There was no significant difference of intervention effectiveness on group size, frequency of sessions, or students’ ages/grades.

Now that we have an overview of the external evidence, let’s dig deeper and find out what intervention approaches were effective. While we walk through a framework for summarizing and main idea interventions, consider which strategies might be a good fit for your caseload.

1. Preview Text Structure

First things first: what kind of texts and materials will be the base of your intervention?

To generate a summary, students will first need a stimulus, such as a picture scene, passage, story, or video. It’s no secret that we love literacy-based therapy (see previous posts here), and there are endless ways to incorporate summarizing skills into this framework. Depending on your students’ ages and interests, you can incorporate photos and paragraphs, narrative texts such as picture books and fiction articles, nonfiction articles with a range of different text structures, or video clips.

Stevens, Park, & Vaughn (2019) suggest that there are benefits of explicitly teaching the text structure of what students are reading (Bakken, J. P., Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E., 1997; Dimino, J., Gersten, R., Carnine, D., & Blake, G., 1990; Weisberg, R., & Balajthy, E., 1990). When students know the context of a story (fiction or nonfiction) or an author’s purpose (to inform, persuade, entertain), it can serve as an effective foundation for summarizing. This can be incorporated during your “book walk” with students — review the type of text you’re reading or ask students to make a prediction. Another option: give students the ability to choose the structure of the text you’ll be targeting! Many of my high school students love the nonfiction units involving debates, so it’s a great chance to explore the structure and intent behind these persuasive texts.

2. Integrate Graphic Organizers

Which visual aids will you use to explicitly teach and practice summarizing skills?

Graphic organizers were observed to support students’ ability to identify main ideas and generate written summaries (Boyle, 1996; Boyle & Weishaar, 1997; Faggella-Luby & Wardwell, 2011).

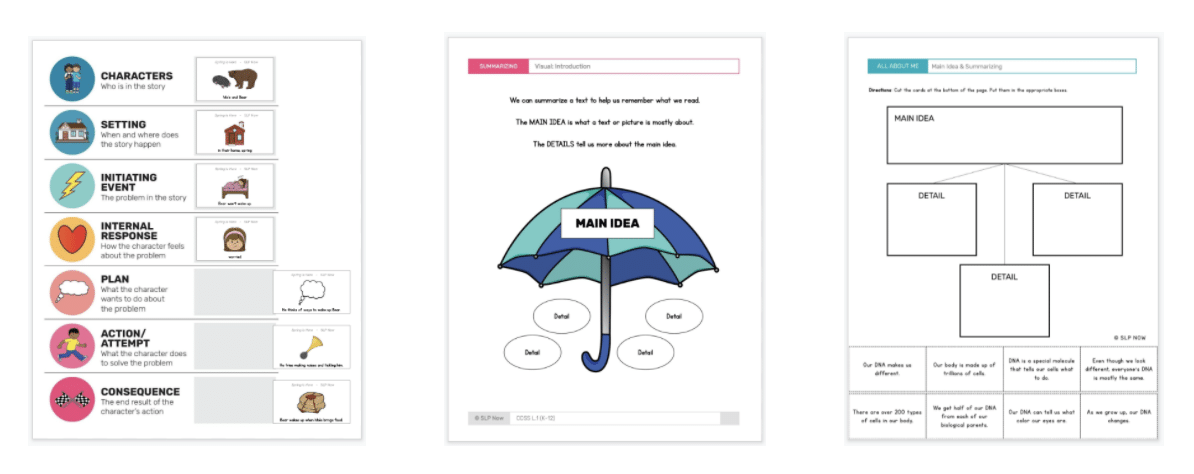

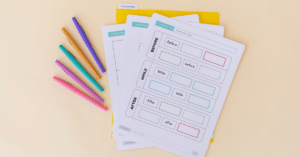

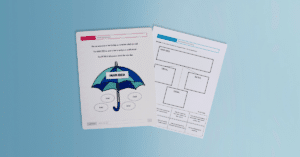

In narrative texts, you may consider story grammar diagrams and sentence starters, which can be found here. Check out these summarizing visuals, which are also adapted for each nonfiction unit. Here are a few graphic organizers in action:

3. Teach Summarizing Strategies

Now that students are primed on the type of text they’re reading and the summarizing tasks at hand, consider equipping them with strategies to use while listening and reading.

Here are a few strategies supported with research:

• Brown & Day’s (1983) Macrorules for Summarizing: Delete trivial information, delete redundant information, generalize information using a categorical name, and select the main idea topic sentence from the text (if it’s not explicitly stated, invent the main idea topic sentence!)

• Schunk & Rice’s (1992) 5-Step Comprehension Strategy: Read the comprehension questions, read the passage to find out what it’s mostly about, think about what the details have in common, imagine what would make a good title, and reread the story if you do not know the answer to a question.

4. Encourage Self-Monitoring

To support students’ progression towards independence, the following self-monitoring strategies were outlined:

• Self-questioning techniques (Graves, 1986): Prompt students to think of a question about the main idea and answer it. Let’s take an article all about sharks: What makes sharks special? How many kinds of sharks are there? Which ones are the most dangerous? Asking and answering these questions about the text can help students generate a summary with key details.

• Checking off completed strategy steps (Jitendra et al., 2000; Malone & Matropieri, 1993): After identifying “who” did “what”, working through a story element diagram, or incorporating summarizing strategies, students can check off each step as complete.

Wrapping it up with a recap!

Let’s recap these researched approaches to targeting summarizing skills:

1. Preview text structure.

2. Integrate graphic organizers.

3. Teach summarizing strategies.

4. Encourage self-monitoring.

This is a snapshot of practical summarizing and main idea intervention strategies captured by the literature over the past few decades. Some of these may already be part of your arsenal and some may be unfamiliar. For what it’s worth, here’s a friendly reminder: none of the research studies tested all of these strategies simultaneously, so there’s no precedent to fit each intervention approach into one activity during your next session. Let us know what you think about the review and if you have any questions. Thanks for stopping by!

References

Bakken, J. P., Mastropieri, M. A., & Scruggs, T. E. (1997). Reading comprehension of expository science material and students with learning disabilities: A comparison of strategies. The Journal of Special Education, 31(3), 300-324.

Boyle, J. R. (1996). The effects of a cognitive mapping strategy on the literal and inferential comprehension of students with mild disabilities. Learning Disability Quarterly, 19(2), 86-98.

Boyle, J. R., & Weishaar, M. (1997). The effects of expert-generated versus student-generated cognitive organizers on the reading comprehension of students with learning disabilities. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice, 12(4), 228-235.

Brown, A. L., & Day, J. D. (1983). Macrorules for summarizing texts: The development of expertise. Journal of verbal learning and verbal behavior, 22(1), 1-14.

Dimino, J., Gersten, R., Carnine, D., & Blake, G. (1990). Story grammar: An approach for promoting at-risk secondary students’ comprehension of literature. The elementary school journal, 91(1), 19-32.

Faggella-Luby, M., & Wardwell, M. (2011). RTI in a middle school: Findings and practical implications of a tier 2 reading comprehension study. Learning Disability Quarterly, 34(1), 35-49.

Graves, A. W. (1986). Effects of direct instruction and metacomprehension training on finding main ideas. Learning Disabilities Research.

Jitendra, A. K., Kay Hoppes, M., & Xin, Y. P. (2000). Enhancing main idea comprehension for students with learning problems: The role of a summarization strategy and self-monitoring instruction. The Journal of Special Education, 34(3), 127-139.

Schunk, D. H., & Rice, J. M. (1992). Influence of reading-comprehension strategy information on children’s achievement outcomes. Learning Disability Quarterly, 15(1), 51-64.

Stevens, E. A., Park, S., & Vaughn, S. (2019). A review of summarizing and main idea interventions for struggling readers in grades 3 through 12: 1978–2016. Remedial and Special Education, 40(3), 131-149.

Weisberg, R., & Balajthy, E. (1990). Development of disabled readers’ metacomprehension ability through summarization training using expository text: Results of three studies. Journal of Reading, Writing, and Learning Disabilities International, 6(2), 117-136.

Perspective taking: “According to the author…”

WH questions: Who / did what / when / where / why

Conjunctions: Someone / Wanted / But / So / Then

Leave a Reply